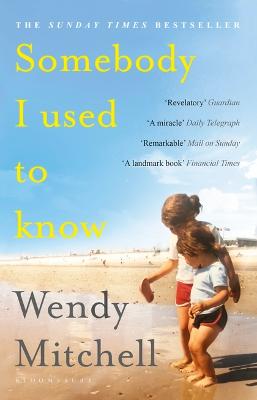

Somebody I Used to Know

Find your local library.

Buy this book from hive.co.uk to support The Reading Agency and local bookshops at no additional cost to you.

How do you build a life when all that you know is changing?

How do you conceive of love when you can no longer recognise those who mean the most to you?

A phenomenal memoir, Somebody I Used to Know is both a heart-rending tribute to the woman Wendy Mitchell once was, and a brave affirmation of the woman dementia has seen her become.

Wyneb Cyfarwydd

Sut ydych chi’n adeiladu bywyd pan fydd popeth rydych chi’n ei wybod yn newid?

Sut ydych chi’n meddwl am gariad pan na allwch chi adnabod y rhai sy’n golygu fwyaf i chi mwyach?

Mae Wyneb Cyfarwydd yn gofiant rhyfeddol, yn deyrnged deimladwy i’r fenyw y bu Wendy Mitchell unwaith, a chyffes ddewr o’r fenyw y mae dementia wedi’i gwneud hi.

Latest reviews

A very powerful book about the impact of living with early-onset Alzheimer's. We were privileged to have the author join our reading group and she reinforced the message that a life of dignity and respect is possible in this situation. Wendy asked the first question, wanting to know why we chose her book and she gave us our first piece of advice- ask other authors to join our reading group, she was sure they’d be delighted to come along! Wendy told us about her amazing experience in writing her book- she’d been asked to write one by the many publishers who found her blog. She knew she needed help to write the book, and her co-author Anna wished she’d written a book of the story of her father with dementia. After their first meeting Wendy described trusting Anna, and not wanting just anyone to write such a personal story. In a nanosecond of meeting they clicked- Wendy responded to Anna’s big beaming smile, and they knew they’d be able to write together. The book was written by Whatsapp and email- the language of emjois was really important. Anna kept things on track and together they’ve just written the second book which covers what happened since the first book, but also includes the voices of her playmates- other people with dementia- to broaden out the voice and allow their stories to be told. Wendy’s experience of her diagnosis was particularly poignant. She felt so alone when first diagnosed, and stressed the need for clinicians to consider the psychological effect of voice and body language. Yes, her diagnosis was difficult, but she could have been given the diagnosis with more positivity- there was a lot of life left to live. She carried on working until she was ready to stop, not when she was told to stop, but she felt let down by the NHS when she needed them the most. Her manager asked how long have you got? Instead of asking how can we help you? In her words, “I may have been diagnosed with young onset dementia, but I was no different the day after the diagnosis than the day before”. She had lots to contribute in those 9 months extra of working. A question from the group asked for advice if we had newly diagnosed colleagues? The answer was not to give up on them, and to create a culture of people being able to approach an empathetic person to tell they’ve been diagnosed. That’s often the fear, approaching and telling about the diagnosis. Another reader asked whether people’s attitudes to Wendy had changed after writing book. Yes, in both good and bad ways. Bad- the opinion that she couldn’t have dementia because she can write a book. Wendy explained that her fingers can type quicker than she can think or speak as that part of her brain hasn’t been affected yet. The positives were overwhelming, she was amazed that people wanted to read her book- we weren’t! Wendy particularly enjoyed the messages she received saying I’m no longer afraid. One from an 83 year old in Hawaii said they now had post-it notes all over their hut to remind them what to do every day. The worst thing to do is wrap the newly diagnosed up in cotton wool- her example was of her daughters helping her to put her coat on, until she realised that she was forgetting how to do it herself. We were interested in Wendy’s research involvement, which was too extensive to recount. She is now a valued co-researcher with a university who have seen the benefit of having someone with lived experience for developing questions, format and encouraging other to take part. People with dementia trust her as she has the same condition. We also found out about her 2 honorary doctorates- she’s a DrDr! Others in our group wanted to applaud Wendy’s book, and for some there was an acknowledgement that it may have helped with the early days of dealing with a parent’s dementia diagnosis. One of our clinical staff wanted to know what the Trust should include in staff training around dementia, and Wendy reminded us of the human side of caring. Her experiences of how confusing it was to get into a hospital bed on an unfamiliar side, and being particularly sensitive to noise, were eye opening. Audiologists can programme hearing aids to turn down the tone that is particularly uncomfortable to someone’s ears, and Wendy told how that had totally changed her reaction to the outside world. Wendy was inspired by seeing someone else with dementia speaking on stage, and really wants others with dementia not to feel alone. During lockdown, she got to know her village by taking daily photos which she has uploaded to the village Facebook group, so that those stuck inside could see how it looked outside. She was first known as the village camera lady before being known as someone with dementia. She wanted them to see her as a person first. We loved having Wendy join us, and her openness and obvious zest for life were contagious, although I’m not sure how many of the group envied her planned tandem paragliding expedition next week.

Join our mailing list

Get our newsletters to stay up to date with programme news, resources, news and more.